The Scottish vessel shortage is driving up development costs and resulting in delays to the development and maintenance of offshore wind projects in Scotland.

In many respects, the general media has had a particular focus on the current energy market and the way in which power prices have been driven up by issues such as the war in Ukraine, gas supply shortages and bouncing back from the global pandemic, all being contributing factors in the escalation of power prices. On the flip side of this increase in power prices, many renewable energy generators are experiencing rising development and maintenance costs, as a result of similar contributing factors.

One additional factor however that is serving to increase costs for offshore developments in particular, is the potential vessel shortage and bottleneck faced by the sector, and this cannot be underestimated. Solving this issue will be of critical importance to the success of not only the ScotWind projects, but also other offshore developments in the UK and globally.

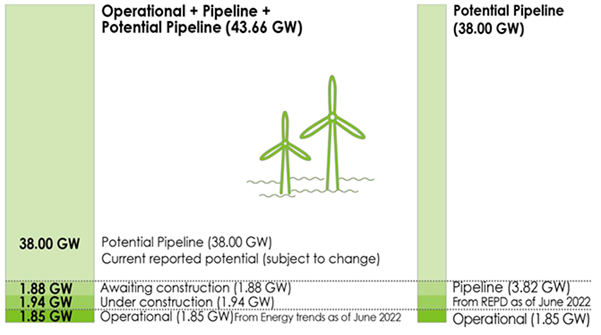

UK government offshore wind operational targets

The UK government has set a target of 50 GW of operational offshore wind generation by 2030. This is an ambitious target to achieve in the next 7-8 years considering we currently have around 4% of the required operational capacity as of June last year, according to the government’s draft energy strategy report.

Despite the contribution of projects currently under construction, it looks unlikely that operational capacity will have significantly increased when the new government report is published later this year.

Source: Chapter 3: Energy supply - Draft Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan 10.01.2023

To ensure we can reach the targets, which will largely rely on Scottish projects, a strong supply chain will be needed. A fundamental part of this supply chain is the availability of vessels to allow for the up-front development of offshore projects, and their continued operation and maintenance. Vessels are used across the lifetime of a project – seabed surveys, transportation of monopiles, delivery of materials, personnel and tools to site to remedy defects, and to decommission the infrastructure when projects come to an end.

We are already beginning to see in the oil and gas sector increased demand for vessels associated with the carrying out of decommissioning work as offshore infrastructure comes to the end of its operational life. The government body Offshore Energies UK predicted in its latest report that 2,100 North Sea oil wells will be decommissioned at a cost of £20bn over the next decade, which again will exacerbate the vessel shortage.

Vessel shortage – the problem

The shortage of supply vessels is already acute and looks to remain this way considering the competing demands of offshore infrastructure. According to shipbroker Clarksons “excluding China, there are currently only about 10 turbine installing ships and a few dozen construction support offshore vessels “CSOVs” operating worldwide. By 2030, demand for turbine installers will outpace supply by about 15 vessels, while the gap for CSOVs will widen to more than 145 CSOVs from 30 currently, it estimates.” This scarcity has created a situation in which offshore developers must allocate contracted ships to either maintain the offshore assets they already hold or develop new offshore wind farms. This adds additional complexity as projects compete internally to ensure they have adequate resource, as well as with competitors developing in the area and overseas.

Vessel suppliers are contracted to work for numerous developers and different competing projects with the same developer. Due to the continued shortage many vessel suppliers are in a strong commercial and contracting position. This creates a situation in which vessel suppliers can insist on higher charge out rates, dictate the window in which the vessel may be used irrespective of whether the vessel can be safely transported to the project site, and can insist on payment of compensation for potential use of the vessel in the form of standby costs.

If a delay occurs outwith the control of the parties – for example adverse weather at the development site, which is a common occurrence in Scotland and the likelihood increases the more northerly the project – they must then negotiate on how this delay will be accommodated. This may result in a termination of the contract and replacement of the supplier, or an extension to the underlying contract. These options in most cases will add additional delays and costs to the offshore project.

The future

The competition for vessel resource is fierce within the offshore sector. Leaving aside the competing demands in the current UK offshore sector, it should also be acknowledged that in Europe alone, the UK, German, French, Polish, Dutch and Belgian governments have a combined wind generation target of 140 GW by 2030.

Stakeholders will need to address the issues effectively to ensure the timely delivery of projects with a return for investors and to achieve net zero targets.

It is likely the issue of vessel supply to the offshore supply chain will continue to remain a stumbling block to a smooth roll-out and development pipeline of offshore projects for the foreseeable future.

If you are a developer or stakeholder and would like further advice in relation to offshore wind projects, negotiating commercial and construction contracts with offshore wind developers and suppliers, or general commercial advice, please get in touch.